Reggae practice is more than just music. It is dance, it is physical engagement, it is culture, it is struggling, and it is a celebration. The sounds of Reggae are perhaps Jamaica’s most well-known and ubiquitous cultural exports.

The history of Reggae as a musical tradition that began as a force of unification in the face of political violence, resistance to oppression, and spiritually uplifting.

Due to the sociocultural situation in which Reggae was founded, its practitioners focus on messages of liberation, political struggle, and cultural celebration.

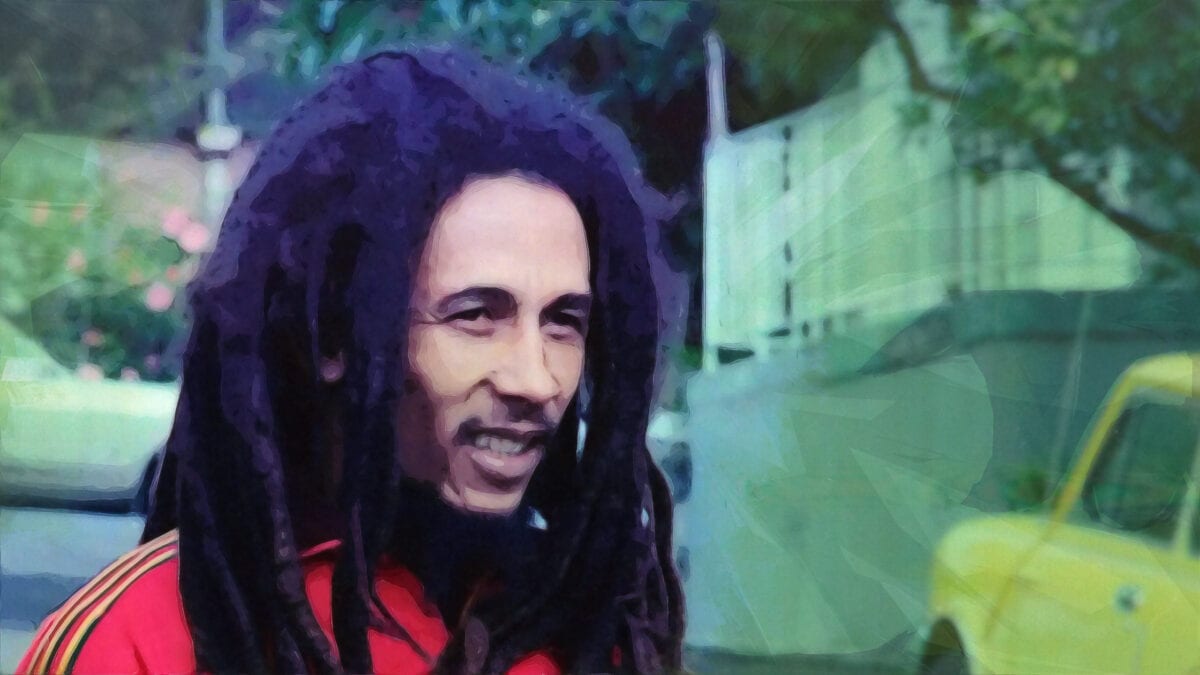

Given the hardship faced by the people of Jamaica, poverty, crime, political corruption, and gang violence, the global rise of reggae music is an awe-inspiring cultural feat: Bob Marley is a household name the world over; Reggae beats pervade pop music in the United States and Europe; Reggae dancehall artists are common on the American top 40 charts; dub music and its subgenres are ubiquitous in electronic music; hip-hop (which owes its beginnings to Jamaican DJs who immigrated to New York City in the 1960s and 70s) is one of the top-selling genres on the planet. These facts alone are a testament to Reggae’s artistic power and Jamaican music broadly.

The Roots of Reggae

Reggae music exists as a sort of creole music, evolving out of Ska, Rock Steady, and dub music. Reggae also draws on the influences of West African burru drumming and American RnB. In contrast to Cuba, another Caribbean nation with powerful musical exports in son and salsa, Jamaica’s musical tradition does not draw heavily on 19th-century creole lineages.

Of course, the history of British slavery of African people in Jamaica is ever-present in cultural expression and is indeed present in Reggae’s practice. However, European’s specific musical mixings with African traditions didn’t begin in Jamaica until the 1950s, placing Reggae near the beginning of Jamaica’s development of creole musical traditions. Authors Peter Manuel and Michael Largey describe Reggae’s late creole development in their book, Caribbean Currents: Caribbean Music From Rumba to Reggae.

Reggae history and prehistory don’t really begin until the 1950s, with the imitation, whether skillful or amateurish, of American RnB…within a generation or two Jamaicans had developed techniques of recording, performing, composing, and dancing that was utterly new, unique, and powerful.

Manuel and Largey, Caribbean Currents: Caribbean Music From Rumba to Reggae.

Reggae music comes out of Jamaican music development, which started in the late 1950s with the popularization of the Ska and Rock Steady genres. These styles of music were designed for dance halls (different from ‘dancehall’ music) and coincided with the beginning of the recording industry in Jamaica. Before the record industry really got started on the island, music was limited mainly to earlier folk traditions, such as burru drumming and mento music (a Jamaican folk music tradition). Of course, dance was an important element of these musical practices, but not designed specifically for the dance hall. Dance halls were social venues popular in the United States and Europe since the 1920s but were not ubiquitous in Jamaica until the 50s.

Ska Music

Ska is widely considered the first indigenous popular music of Jamaica. Moving away from American RnB and West African traditional roots, Ska asserted itself as a genuinely Jamaican musical form. The backbone of Ska music is the interaction of the drums and bass. Perhaps the primary development of Ska music, as opposed to Rnb, is the drummer’s accent of the ‘off beat’ on the hi-hat. At the same time, the bass player maintains the strength of beats 1 and 3. This drum and bass interaction carries through all the way into reggae music and is one of the most recognizable musical characteristics associated with the genre.

Another important musical aspect of Ska music is the inclusion of a horn section, usually saxophone, trombone, and trumpet. Ska music asserted a national Jamaican identity and sparked decades of musical development within Jamaica, as well as a later Ska revival within the United States (both in the pop and punk spheres).

A quintessential example of early Ska performance is Laurel Aitken’s 1963 recording of the song, “Zion City Wall.” This song exists as an expression of a religious and celebratory outlook of returning to the promised land, while also providing a strong dance groove, based on the drum and bass interaction.

Rock Steady Music

Rock Steady music exists as a sort of mid-point between Ska and Reggae. In structure, it is quite similar to Ska, but with slower beats (sometimes at half of Ska’s tempo). The slowing of the tempo serves two functions:

- It allows for greater differentiation between the drum’ off beats’ and the strong bass beats, which actually amplifies the strength of their interaction.

- The slow tempo also allows for ease of dancing. Ska’s fast rhythms can be tricky, especially for partner dancing.

Other changes between Ska and Rock Steady include the addition of percussive guitar playing on the ‘off beats‘ to add emphasis along with the drums and the replacement of the horn section with keyboards. These changes were not ubiquitous within the Rock Steady genre but were common.

What really came to the forefront in Rock Steady were the lyrics. Ska lyrics tended to focus on, love, celebration, and some religious jubilance. While this is still true in Rock Steady music, the political elements of Jamaican identity, street culture, ‘rude boy‘, and Rastafari themes became increasingly common in lyrical composition. Bands such as The Heptones, The Paragons, and The Techniques exemplify the Rock Steady style. The Heptones’ 1973 song, “Book of Rules” displays these musical and lyrical shifts, introducing social and Rastafarian themes into their music.

The Religion of Rastafari

Rastafari is a religious movement on the basis of reggae culture. Rasta comes out of the teachings of Marcus Garvey, dating back to the late 1880s. These teachings included black pride, social mobilization, and worker’s rights. A major aspect of Garvey’s teachings was a return to Africa of the diasporic populations. This idea can be ever-present in the lyrics of Reggae, Rock Steady, and Ska.

Discussions of Zion, the ‘holy land’ of Africa (primarily Ethiopia), and the Exodus refer to Garvey’s teachings of a return. Garvey is seen as a prophet of the Rastafarian faith, a sort of creole in and of itself, building on Christian roots with influences of other traditional belief systems stemming from Africa.

The name, Rastafari, comes out of Garvey’s prophecy that an African King will liberate the diaspora and bring them to salvation. Rastafarians believe this king was Haile Selassie (originally named Ras Tafari Makonnen). Selassie claimed himself emperor of Ethiopia in 1930 and ruled until 1974. Many reggae musicians venerated Selassie in their lyrics. Bob Marley actually belonged to a Rastafarian sect, The Twelve Tribes, that believed that Selassie was Jesus Christ, returned to earth.

Many of the cultural practices associated with reggae music come from Rastafari. Long dreadlocked hair comes out of a semi-biblical prescription for not cutting nor preventing it from braiding. Prohibitions on drinking and reverence for pastoral living come out of Rastafarian culture as well. Many terms common in reggae lyrics also are derived from Rasta traditions: Babylon refers to Jamaica, the land in opposition to Zion, where the people lay and wait for their return; Jah refers to god; and ‘I and I’ is a phrase referring to the physical self and the spiritual self.

Reggae singer Bob Andy was an early pioneer of the inclusion of explicitly Rastafarian themes in his music. Lyrics like I’ve got to go back home, This couldn’t be my home, It must be somewhere else, Or I would kill myself

refer to his misplacement in Babylon when he should be in Zion. This longing for home and depression felt in post-colonial society are hallmarks are Rastafarian lyrical writing in reggae music.

Dub and the Roots Reggae Era

In the late 60s, Jamaican DJs began to develop a process of pairing down a mix to its essential drum and bass foundations. This technique was used in dance halls and parties, allowing people to sing along to the songs they loved (kind of like a crowd karaoke) and allowing DJs to ‘toast’ (or rap) over rhythm tracks. This history would ultimately lead to the hip-hop revolution in New York, about a decade later. However, in Jamaica, it would spark the rise of the roots reggae movement. The rhythm tracks created in these dub mixes became the basis for reggae composition. They would tie the lineages of Reggae to hip-hop/electronic music for decades.

Just as the move from Ska to Rock Steady brought with it more socially conscious lyric work, the roots nature of dub toasts (raps) took this even further. Laying the groundwork for reggae subject matter from the 1970s on.

Big Youth was an early pioneer in dub music, toasting over popular Jamaican records on subjects relating to uplifting Jamaican society, Pan-African identity, and political struggle. His 1973 song “Screaming Target” is a dub on K.C. White’s “No, No, No.” Big Youth uses the dubbed rhythm from White’s record to rap about the need for education and the social problems created by ignorance.

Big Youth – Screaming Target

K.C. White’s “No, No, No

Following the technological and musical developments of dub came a host of roots reggae artists creating music based on the dubs being created by DJs and unabashedly celebrating Rastafarian identity, socially and politically. Some of the most important early roots reggae artists include Toots and The Maytals, The Abyssinians, Black Uhuru, Desmond Dekker, and of course, Bob Marley and The Wailers.

Bob Marley – Reggae’s Global Explosion

Bob Marley And The Wailers (originally called The Wailing Wailers) is undoubtedly the most famous Reggae group to come out of Jamaica. Their export of roots reggae not just to the United States but to the entire world, is a testament to the strength of their music and message. The Wailers began as a Ska band in 1963, created by Bob Marley (vocals) and Peter Tosh (guitar). Over the coming decade, their sound evolved with the changing music scene in Jamaica, incorporating Rock Steady and dub influences to create their recognizable reggae sound.

Both Marley and Tosh grew up in Kingston’s Trenchtown, a neighborhood known for its extreme crime and poverty and as the birthplace of reggae music. Their life in this neighborhood would influence their music over the course of their careers, pushing them to explore the hardships they faced and advocate for the young people caught up in gang violence and poverty in this community. An example of this is The Wailers’ 1965 song, “Simmer Down,” a directive to the ‘rude boys’ of Trenchtown to calm the violence lest they get killed themselves. Marley’s Ska roots can clearly be heard in this track, in the fast tempo and dance groove. While this song sounds quite different from Marley and The Wailers’ sound from the 1970s and 80s, the lyrics’ social conscience is clear. It remains present in Marley’s writing until his death.

Simmer down, you lickin’ too hot, so

The Wailing Wailers “Simmer Down” – 1965

Simmer down, soon you’ll get dropped, so

Simmer down, can you hear what I say

Simmer down, that why won’t you, why won’t you, why won’t you

The 1970s was an extremely creative time for Bob Marley and The Wailers. 1973 saw the release of two major albums Catch A Fire and Burnin‘. These albums brought massive popular hits that are still in circulation today: “Stir It Up,” “Get Up Stand Up, “and “I Shot The Sherriff.” These songs began gaining international attention for the group. Eric Clapton‘s 1974 cover of “I Shot The Sherriff” boosted Bob Marley and The Wailers even further. Throughout the 70s, The Wailers were touring internationally and putting out some of their most well-known music, Exodus (1977). It was perhaps their most influential and important.

The album, Exodus, draws on Garvey’s theories of return to Africa, with the invocation of the biblical Israelites. This album is a Rasta at its core, exploring religious concepts, social activism, Pan-African celebration, and unity. The first side of the album ends with the song, “Exodus,” where Marley describes the return to Africa from Jamaica.

Exodus, movement of Jah people! Oh, yeah!

Bob Marley and The Wailers “Exodus” (1977)

(Movement of Jah people!) Send us another brother Moses!

(Movement of Jah people!) From across the Red Sea!

(Movement of Jah people!) Send us another brother Moses!

(Movement of Jah people!) From across the Red Sea!

Movement of Jah people!

The second side of the album ends with the song “One Love/People Get Ready,” celebrating the unity of Pan-African identity in a message of love for one another (and humankind).

One Love! What about the one heart? One Heart!

– Bob Marley and The Wailers “One Love/People Get Ready” (1977)

What about – ? Let’s get together and feel all right

As it was in the beginning (One Love!)

So shall it be in the end (One Heart!)

All right!

Give thanks and praise to the Lord and I will feel all right

Let’s get together and feel all right

As Marley rose to international stardom, he was unable to escape political violence and health problems. Marley survived an assassination attempt in 1976, where he was shot near his heart, luckily not hitting it. Sadly, his health suffered after the incident. In 1977, Marley was diagnosed with cancer, and in 1981, Marley lost the battle while attempting to make it back to Jamaica from Europe. Even though Marley died early, his lasting effect on Reggae and global music is undeniable.

Reggae’s Interactions With Punk

The 1970s saw the rise of many new forms of music, including the punk revolution in England. As Great Britain saw a significant influx of immigrants from Jamaica starting in the 1970s, reggae music had a place in the English musical landscape. The roots reggae band, Steel Pulse, actually formed in Birmingham, UK, of all places and had a uniquely British quality. Their music directly addressed issues of blatant racism experienced at the hands of the police and society broadly. Their song, “Ku Klux Klan,” in no uncertain terms, addressed the racial violence experienced by black people throughout the western world.

As both reggae and punk address similar issues of disenfranchisement, political struggle, and the rights of the downtrodden, there was a natural relationship between the genres. Obviously, the punk attitude is somewhat more outwardly aggressive than Reggae, but the outlook is the same in many ways. In fact, Steel Pulse often toured and performed on shows with punk bands. By the late 1970s, many British punk bands had adopted certain reggae practices – fast off-beat rhythms, reggae riffs, and even Rasta inspired language. The punk band, The Ruts, in their song “Babylon’s Burning,” describes the destruction of Rastafarian Babylon.

Interestingly, this marriage of genre was social as well as musical. After the breakup of The Sex Pistols, Johnny Rotten decided to retire to Jamaica.

The relationship between Reggae and punk continued into the 1990s with the rise of the punk-Ska bands: Reel Big Fish, Less Than Jake, Sublime, Mr. Bungle, The Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Cake, and others. This development brought back the horn sections present in Ska music, while maintaining the fast off-beat guitar patterns of Reggae, and the harsh attitudes of punk. Reggae influences are even present in more straight-ahead punk music, specifically in the drum and guitar work. Bands like NOFX, The Clash, and The Dead Kennedys all draw on musical elements from Reggae.

Reggae, Hip-Hip, and Dancehall Music

Reggae and hip-hop are inexorably connected in many ways. One way of viewing these two musical traditions is like two sides of the same coin, both stemming from their Jamaican dub roots. Traditional hip-hop is, in many ways, an Americanized version of Jamaican dub practice, with performers rapping (or toasting) over rhythm sections of classic records. Even hip-hop’s origins come from Jamaican DJs performing dub style music at dance parties in The Bronx, New York City, in the 1970s. DJ Kool Herc is probably the most well-known of these early hip-hop Jamaican DJs. Herc is credited with both starting what is now called hip-hop.

The late 1970s aw a synthesis of Reggae and hip-hop, leading to a new style of music – dancehall. Dancehall music is very tied in with hip-hop, and many dancehall musicians perform and tour with hip-hop artists. While roots reggae is very spiritually conscious, dancehall is very sensually conscious. The lyrics of early dancehall music are explicitly sexual and sensual. Many of the socially uplifting messages of roots music shifted into more hip-hop like celebrations of street culture – including gang life, drug use, and sexual objectification.

An important aspect that separates dancehall from hip-hop is that dancehall maintains the tradition of singing, coming out of its reggae background. Dancehall songs are often a mix between singing and rapping, while many traditional hip-hop tunes are exclusively rapped. While this differentiation exists, dancehall music is rhythmically very tied into hip-hop. While roots reggae maintained the Rock Steady rhythms of the ‘on beat’ and ‘off beat’ interaction, dancehall rhythms were based on a more hip-hop centered dance groove (a repeating dotted rhythm pattern).

Tracks like “Boom Bye Bye” (1995) by Buju Banton and “Welcome To Jamrock” (2005) by Damien “Jr. Gong” Marley, clearly display this combination of Reggae and hip-hop in dancehall music, coming out of their dub lineages.

Boom Bye Bye by Buju Banton

The 1990s saw the integration of dancehall style into American pop music. Throughout the 90s, dancehall artists were featured in many top 40 tracks. By the 2000s, artists like Damien Marley, Pit Bull, and Shaggy were ubiquitous in the pop music world. Many non-dancehall artists create music that references this tradition. Even artists like Drake and Rihanna frequently draw on dancehall style.

Welcome To Jamrock by Damien “Jr. Gong” Marley

Conclusion

The influence that Reggae has had on the global music scene is hard to understate. Obviously, a short essay like this can only address some of the essential aspects of this complex musical tradition and its influences. In the current musical landscape, Reggae can be found everywhere, from electronic dance music to heavy metal to contemporary classical music. Part of the power of this musical tradition comes out of its strong messages of unity, spirituality, sensuality, love, dance, and struggle.

Sources

- Aimers, Jim. The Cultural Significance of Reggae. Miami University, 2004.

- Biography.com Editors. “Bob Marley“. Biography.com. A&E Networks Television. 18 Aug. 2020.

- Davis, Stephen. “Reggae.” Grove Music Online. 2001. Oxford University Press.

- Degiorgio, Kirk. “The Roots of Dub.” Red Bull Music Academy Daily. 24 Aug. 2018.

- Manuel, Peter. Largey, Michael. Caribbean Currents: Caribbean Music from Rumba to Reggae. Temple University Press. 2012.

- Moskowitz, David A. Caribean Popular Music: An Encyclopedia of Reggae, Mento, Ska, Rock Steady, and Dancehall. Greenwood Press. 2006.

- Music House. “Roots, Reggae, Rebellion Full BBC Documentary“. YouTube. 2017.

- Sound Check. “Punk Rock and Reggae: A Love Story in 2 Acts“. AFROPUNK, 28 Sept. 2012.