Jazz Practice: It’s All The Blues

Both Jazz and Blues traditions share a long and complicated musical history, with roots tracing back to, and even before, the European slave trade of African populations in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Looking at the history of Jazz and Blues, both of these musical forms started as Black American artistic expressions, developed in the face of hardship, discrimination, and slavery. Let’s take a look at how Blues has influenced Jazz.

Throughout the decades, Jazz composers and musicians have developed a complex practice owing a tremendous amount to what it learned from the Blues—moving from big bands to bebop, to modal Jazz, to free Jazz, to modern experiments in future Jazz).

Where Did Blues Come From?

The Blues’ roots came out of the intersection of African diasporic music, southern American church gospel traditions, and country/folk traditions from the American south. Blues as a musical form draws on each of these traditions to create a mode of expression that explores the personal pain and hardships of life, specifically the Black experience in the American south.

Over time though, Blues traditions extended outside of the American south, exported via Ragtime, Jazz, Country, Folk, Rock ‘N’ Roll, Gospel, and other popular music forms. Eventually becoming a globally recognized style and genre.

Black American Musical Traditions

Blues’ influence in Jazz is particularly interesting because these are both Black American musical traditions, sharing many lineages and being somewhat distinct from each other. Jazz, as a musical practice, draws deeply on Blues’ language, culture, and history. In fact, one could argue that there could be no Jazz without the Blues.

Jazz does, however, also poses strong ties firmly to European instrumentations and harmonies. Many of the lead instruments used in Jazz music come from European classical traditions – trumpets, saxophones, trombones, pianos, and the modern drum set.

The Jazz and Blues Harmony

While often quite advanced compared to its European counterparts, the triadic nature of Jazz harmony is based on somewhat classical constructions of chords. This comparative harmonic complexity of Jazz could be due to its roots in the Blues.

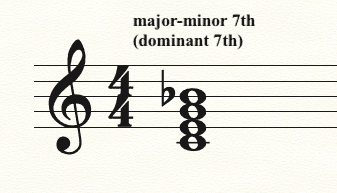

Blues harmony is built on the principle of major/minor obfuscation – meaning that major keys and minor keys blur into one. The Blues’ basic harmonic unit is a major-minor 7th chord, more commonly called a dominant 7th, which has at its base a major triad (shown in figure 1). In classical European harmony, the dominant 7th chord serves to pull back to the tonic of a scale.

Every chord in the Blues has this major-minor 7th quality. Its effect of pulling back to the tonic is destroyed while also maintaining a sort of tension throughout. That unease or tension is part of the musical quality that gives the Blues its character. It is simultaneously still and uneasy.

The Addition of ‘blue’ Notes

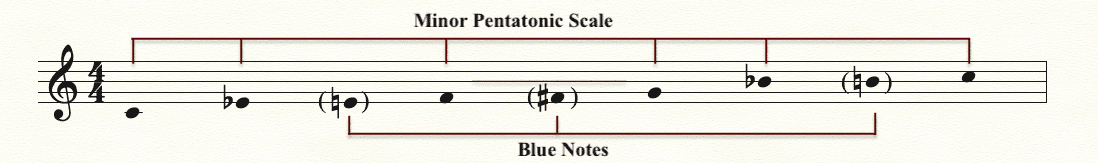

A further harmonic complexity that Jazz derives from Blues practice is the addition of ‘blue’ notes. Blues melodies performed (traditionally sung) over major-minor 7th chords generally use a pentatonic minor scale, with added notes in-between basic scale tones – ‘blue’ notes. These ‘blue’ notes allow for expressive bending, sliding, and shifting to and away from notes that are a whole-step apart (shown in figure 2). These added notes expand the harmonic language drastically. They expose notes in-between those of the traditional pentatonic scale structure, which would traditionally be associated with classical dominant 7th chords.

In many ways, Jazz owes its expansive harmonic language of complex chords and melodic lines to these basic, but deep, Blues principles.

The Personal Nature of Blues

One more element of the Blues that is crucial to understanding its practice is the personal nature of. The songs traditionally come from the first-person perspective. In other words, it’s I have the blues,

not you have the blues,

or we have the blues.

The personal blues can be related to lost love, financial hardship, societal frustration, or political oppression. When B.B. King sings “Every Day I Have The Blues,” his lyrics are:

Everyday, everyday I have the blues

Every Day I Have The Blues,” his lyrics

Everyday, everyday I have the blues

When you see me worried baby

Because it’s you I hate to lose

B.B. King is expressing the blues that he personally has. That individual expression is important. This practice can be seen in Jazz in how personal soloist language is. When John Coltrane solos over his tune “Blue Trane,” he is also giving his personal statements of the Blues, but through his saxophone rather than his singing voice. The same is true for Thelonious Monk on “Blue Monk” or Miles Davis on “Freddie Freeloader” or any practicing Jazz musician for that matter. Each musician’s musical language is unique, and that authentic personal expression is crucial to both Blues and Jazz culture.

The Structure of Jazz vs Blues

Many Jazz musicians, comment on the essential Blues structure of their practice. In Eric Porter’s book What Is This Thing Called Jazz? he describes a Wynton Marsalis tribute to Duke Ellington. Marsalis describes Ellington’s relation to the Blues, …the blues represented the most important color on Ellington’s musical palette, indicating a firm grounding in the African American vernacular…

.

Even a Jazz musician as seemingly avant-garde as Cecil Taylor ties his practice directly in with the Blues. In an interview conducted by A.B. Spellman for his pivotal book, Four Jazz Lives, Taylor describes his desire, wish[ing] people would listen to the essential blues content of his music instead of to whatever forms and devices he may have brought over from the conservatory.

A Forever Lasting Marriage Between Jazz and Blues

While the Blues and Jazz are not necessarily one and the same at all times, the conceptual marriage between the two is essentially unbreakable. As we have seen, Jazz has been in an in-depth dialogue with Blues practice since its inception in the 19th century. The lines between these two forms are continually being blurred.

Many Jazz classics are themselves written in 12-bar Blues form (or numerous variations on it). Many harmonic, modal, and gestural choices in Jazz composition and improvisation come directly out of the Blues. Jazz soloists work their entire careers building their unique musical voices and languages to be able to personally express their own Blues. And indeed, many Jazz musicians themselves view their practice as being essentially Blues in and of itself.

Sources

- Bowden, Marshall. “Blues Music, Ragtime & the Origins of Jazz.” New Directions In Music, 5 May 2019, www.newdirectionsinmusic.com/blues-music-ragtime/.

- Murray, Albert, et al. Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues. Edited by Paul Devlin, University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

- Porter, Eric. What Is This Thing Called Jazz?: African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists. University of California Press, 2002.